Reprieve or Par for the Course | Lesson in Leverage

Thanks for reading another edition of Axe’s Take!

A warm welcome to our 10+ new subscribers these past 2 months. Feel free to pass the blog along to a colleague or friend who would appreciate a financial markets refresher and educational topics on investing.

Market Update (12.7.2022):

YTD Performance by Index:

S&P 500: -17%

Nasdaq: -29%

DJIA: -7%

Back in mid-October, the Bloomberg Economics Probability of a US Recession Within 12 Months Indicator (what a mouthful) hit 100%. Most sell-side research and news outlets seemed to be echoing the same prediction, although there are varying opinions on whether a recession will hit in Q1 2023 or by Q4 2023-Q1 2024. While this is what the Fed aims to bring about (to loosen the labor market to bring down inflation), the first thing that came to mind when I saw the “100% Probability of a Recession” headline was Ben Franklin’s quote:

“In this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes.”

The CPI Indicator, the broad-based inflation measure, came in at a “cooling” 7.7% YoY rate in October. The word “peak” was subsequently thrown around and market participants saw a several-week market rebound and reversal in widening yield spreads (the margin between return on debt instruments of Corporations versus US Treasuries — used as a measure of expected credit risk). This week has begun with a few stark trading sessions to offset the multi-week rebound.

Many anecdotes (tech layoffs, Monthly Credit Card data, weaker guidance from corporates, slowing housing market, downward revisions in Analyst estimates) and financial indicators such as the renowned 10-year/3-month US treasury yield curve inversion are flashing red and may be foretelling a future that the Fed wants to see. A resilient labor market, on the other hand, has stemmed fears that the Fed’s work is not yet complete and it will take more hikes than expectations to level inflation.

As mentioned in prior posts, and a foundational concept in my investing approach, short-term macro movements are nearly impossible to predict, are often random in nature, and should have little bearing on long-term allocation decisions (other than using the volatility as a buying opportunity…thank you, Mr. Market).

A positive CPI report is encouraging, but the Fed’s inevitable pivot may be longer away than the market believes if inflation ends up being stickier than expected and the job market refuses to cool down. The Fed’s initial stated goal was to bring inflation back to its 2% target — an unthinkable target if you ask most investors today unless the Fed intends to magnify its hawkish stance (i.e. aggressive monetary policy) and test the fragility of the American economy.

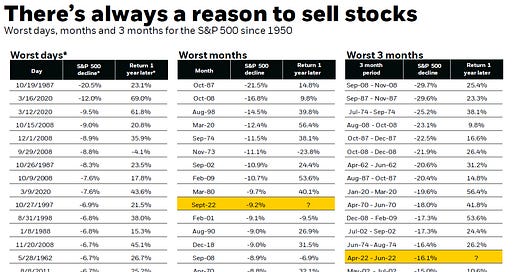

A function of bear markets is intermittent swinging back to the green throughout their life cycles. Some of the best market days EVER occurred during the worst market routs. These movements tend to confuse market timers — the bipolar nature of Mr. Market and the complexity of the economic system can convert the staunchest bulls and bears over a market cycle to the other side for a short period of time…and back again. The below slide from BlackRock provides historical precedents for those wondering “what comes next” after a market downturn:

Since public markets investing is a function of how you behave before and after the financial decisions, it’s important to recognize how you might behave if stuff does hit the fan (if it hasn’t already, if you have technology or small-cap growth exposure in your portfolio, or even if you’re holding bonds).

Howard Marks puts some of the above commentary eloquently in his latest memo. He hones in on the idea that market prices reflect current expectations of the future versus what will actually happen. Therefore, “it’s very difficult to know which expectations regarding events are already incorporated in security prices.” This is the art of investing — parsing out what is priced in versus a variant view of the future will create a beneficial outcome when it materializes.

I’ll wrap up the Market Update with a quote from the “father of value investing,” Benjamin Graham:

“Investment is most intelligent when it is most businesslike.”

Treat your investment decisions like you would if you were dealing with an ownership stake in a business versus basing them on the general mood of the market. Much of the general investing philosophy from this blog stems from this quote.

Thinking about Leverage

As CEOs of banks and financial economists expect a recession at some point in 2023 I thought it would be valuable to introduce the topic of leverage. I mentioned the topic in passing in an earlier post when discussing some of the key qualities investors look for in businesses.

While the proverbial music plays and economic times are good leverage is looked at as an opportunity. For private equity investors who employ leverage in their purchases of businesses, or corporations who use leverage to pursue capital expenditures or manage their capital structure, leverage is a helpful tool.

For the corporation, it “costs” less than issuing equity given the contractual obligation of the debtor to the creditor and the lower expected return the creditor is satisfied with. This contractual right to interest payments and principal at maturity is a draw for certain investors who want contractual protection and a fixed stream of payments.

When cash flow is flush and a business is growing, being highly levered (i.e. high quantum of debt on the Balance Sheet relative to earnings) isn’t really an issue. It could even present an opportunity to equity investors in the case of a business paying down its debt from its highly levered state. As discussed in this paper there is a pattern of relative outperformance for public companies that are in process of paying down debt.

Bond Investing Overview | When the Music Stops

I will quickly review how one might go about thinking about investing in an individual bond and then get to the above.

To keep things simple, when a company issues debt it usually comes with a prescribed coupon rate that it will pay to the holders of the debt as well as a pre-determined principal amount (i.e. $100MM at 6%).

Outside of the initial issuance (primary market) of a company’s bond, there is a secondary market where just like stocks, buyers and sellers of publicly traded bonds will come together to buy/sell already issued bonds that each pay out a certain coupon. In a perfect state, bonds will trade at par value ($100 or 100 cents on the dollar). This means the market believes the company is fully capable of paying off the bond upon maturity. [I’m intentionally ignoring the influence of moving interest rates and incremental issuances, which influence bond prices, both above and below par.]

The maturity date is the date by which the company owes the holders of the bonds the Principal amount (the initial loan they made to the company when they bought its debt). If there is doubt that the company will be able to pay back the Principal the bonds may trade below Par ($80 price versus $100, for example).

Imagine a bond trading at $80 with an annual coupon rate of 6% that matures in December 2023. A buyer of that bond will expect to “clip” a 6% coupon per year before maturity. In addition, at maturity, the company is obligated to pay her the initial Principal (i.e. the Par value of $100). Therefore, by buying a bond trading below par, an investor could recognize a yield above the simple coupon rate. She’ll receive a 6% coupon as well as a Principal payment of 20% above the price she paid. Without adding more complexity the common term for calculating this yield is yield-to-maturity (YTM).

With that explanation behind us, what happens when the music stops?

Companies rely on business performance to pay interest expenses. If business slows, interest payments do not slow. The obligation remains. Think of leverage like a collar on a dog. The dog is constrained to the length of the leash. So too is a company constrained to the magnitude of its interest payments and debt balance. It doesn’t stop there. Remember the concept of maturity? Not only does the company need to pay its interest obligations but if a bond or loan is maturing in the near term the company needs to use its cash to satisfy the Principal obligation. Let’s say, due to a slowing business environment and increased use of cash, the company can’t afford to pay back the entire Principal. This is when you’ll hear terms like liquidity risk, bankruptcy, and liquidation start to be used.

Therein lies a challenge that an entire sub-sector of finance is focused on (Restructuring Advisory and Distressed Credit Investors, for example). I will let ChatGPT explain further:

The point of this piece is that companies, run by humans, will often extrapolate profitable, easy times and take on debt to take advantage of the wonderful aforementioned benefits of leverage. When the music is playing this works. However, when the music stops, which is what consensus believes will happen in the next 12 months (to varying degrees) extrapolation turns into desperation.

Companies that run into a maturity wall (an amount of debt maturing in a defined period of time) at the same time that growth is coming to a halt and markets are adherent to incremental lending will face issues and higher risks of bankruptcy (i.e. their publicly traded bonds will decline further, increasing the YTM). When understanding companies for investment it’s important to think about which ones have an unhealthy degree of leverage, and if they do, which ones operate a business that is ultra-sensitive to macroeconomic shifts and what the repercussions would be. The downside scenario is important if you are trying to protect your capital. That is the true risk as defined by value-oriented investors.

The same ills of extrapolations play a role in macroeconomic forecasting. It’s a bias that is hard to avoid. If recent price action is up and to the right people will assume conditions have improved or the outlook is healed. Once assets fall for a few days people will forget their reversal of opinion and return to despondency. Understanding why you think what you do and what that might be influenced by is an important point to keep in mind. Momentum is strong until it isn’t.

Informative Articles/Tweets:

Historical and Future Trends in Data Systems

Disclaimer: The information on this Site is provided for information only and does not constitute, and should not be construed as, investment advice or a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any investment including any products or services or an invitation, offer or solicitation to engage in any investment activity. The opinions stated above are solely the opinion of the author and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the author’s employer.